By guest writer Melvyn Foo.

On all my holidays this year, my routine when I return to our accommodation is the same. I transfer the photos from my camera’s SD card to my laptop, I edit and select them, and then I upload them to Bonjournal1 and complete my travel log.

In the course of this most recent trip, I have come to call this routine ‘reaping the harvest’. By corollary, then, the day’s experiences are the seeds sown, the harvest of which are the memories that I immortalise in the web.

I have been asked repeatedly why I am so obsessive about archiving my life. I sometimes reply, “The unarchived life is not worth living.”

Remove the double negatives, rearrange, and you get something less tongue-in-cheek and more defensible: life is worth archiving.

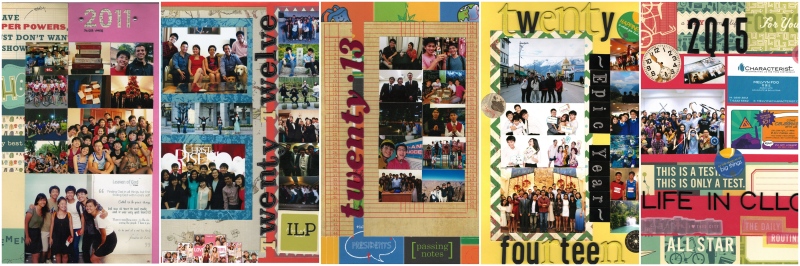

Scrapbooking is the epitome of archiving memories. You choose the happy snapshots, you write nice words, and you frame everything in a pretty page – exactly how you would like to remember those moments.

I am not good at scrapbooking. I took a course years ago, and since then, I have concluded that I have no natural talent for it. I take hours to do what the artsy girls can do in minutes (e.g. choosing paper). I work laboriously (e.g. take exact dimensions) to do what they do by sheer guesstimation. I use science (e.g. rule of thirds, triangulation) to do what they do by feel. (I have since learnt that you can’t really plan every detail out, so you just have to make decisions and improvise along the way. This works sometimes, and sometimes it doesn’t. After all, just like jazz, improvisation requires talent, which I lack.)

It does not help that I have color disorder.

Despite my difficulties, I am still drawn to scrapbooking. I have a drawer full of materials, I have a Paper Market membership card (which may have expired), and I scrapbook a cover page for each year’s journal (which comprises largely of blogposts that I compile and print out).

Why? Why is the past – not just knowing what actually happened but remembering what happened – so important?

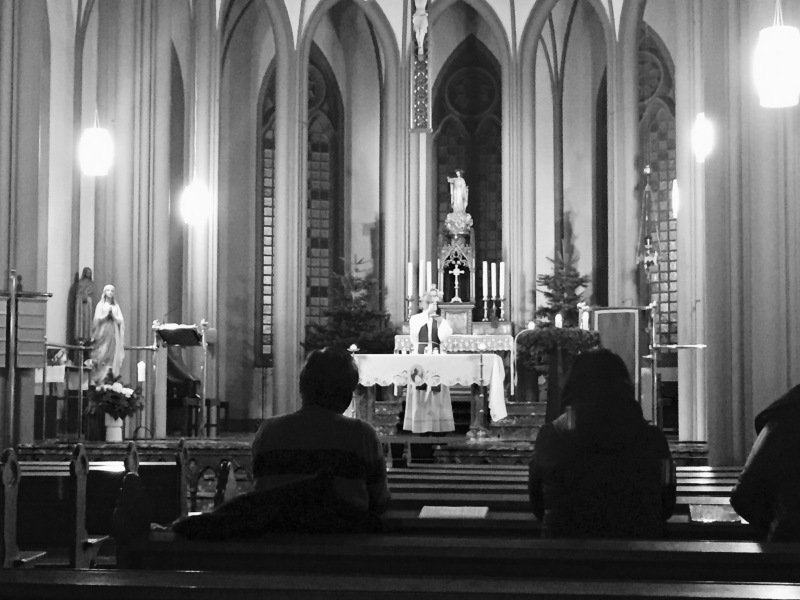

An answer may be found in an unlikeliest of places: Catholic liturgy.

In every Mass, Catholics take Jesus’ words literally to “do this,” – i.e. to eat His body and drink His blood – “in remembrance of [Him].”2 This is not just symbolic. The Church holds that the Mass re-presents Jesus’ sacrifice on Golgotha.3 Father Jude had thus alluded in a talk on how there is only one Mass and “one single sacrifice”4 – the one on Golgotha – that we remember and re-present in all our Masses.

This remembrance and re-presentation is called anamnesis, which comprises the heart of the Eucharist.5 The word, sharing a similar etymology with ‘amnesia’, means “a calling to mind, remembrance”.

This word is also used in philosophy and in medicine. In philosophy, it is a Platonic concept which conceives of learning as a rediscovery of knowledge within us from past incarnations. In medicine, it refers to a patient’s medical history which a physician needs to know in order to diagnose and care for that patient.

Regardless of context, the point is the same: when we recall the past, we affect our present and our future. This is the power and the importance of memory.

Transitional justice is an emerging field which increasingly recognizes the critical importance of memory (alongside the four traditional elements of truth, justice, reparation, and guarantees of non-recurrence). This field studies the various processes by which a community recovers from large-scale human rights abuses. With the hindsight from Rwanda, Timor Leste, the former Yugoslavia, et al., it is now incontrovertible that criminal prosecutions alone, while necessary, are far from sufficient. More is required.

Memorialisation is one such process.

Professor Ariel Dulitzky thus wrote that “[c]ertain standards of the United Nations insist on the duty of remembering, educating about the past and rejecting negations of atrocities. They also highlight the role that archives play in the search of truth and justice, and they are also essential for recovering and building memory.”6

This is not just pure sentimentality. Professor Dulitzky quotes the UN Rapporteur on Truth, Justice, Reparation and Guarantees of Non-recurrence, who says that “[it] does not suffice to acknowledge the suffering and strength of the victims,” and concludes that “ultimately, the challenge for a policy of memory is not building memorials or installing sleepy statues, but creating more fair, egalitarian and democratic societies.”7

Again, the point here is: remembering the past determines the present and charts the course for the future.

And yet, if all that is required is to recollect objective historical facts, it is surprising that judicial rulings are insufficient. After all, the trial is democracy’s most potent fact-finding procedure. Why is more – in the likes of film, theatre, museums, etc – required?

In 2001, my family and another family got into a bad accident in South Africa. Both families were traveling together in a single vehicle. The tyre burst, the vehicle ran off the road, hit into barbed wire, and flipped a couple of times. We later learnt that the other family’s dad had been thrown out of the vehicle, and the vehicle had crushed his lungs, killing him instantly.

Two years later, they sued my dad, who had been driving the vehicle at the time of the accident. The judgment arising from the suit is reported as Loh Luan Choo Betsy (alias Loh Baby) (administratrix of the estate of Lim Him Long) and others v Foo Wah Jek [2004] SGHC 230; [2005] 1 SLR(R) 64. It is 18 pages long, and it goes through the evidence in detail. It mentions so much.

And yet it mentions so little. It does not mention the red-stained t-shirt that my mum had used to soak up the blood that had welled out when she performed CPR on their dad, which I had included in an essay based on this accident that I wrote in Secondary 4. It also does not mention a detail that I always talk about when I shared about this accident, that is, how fine the sand was, and how it got into my fingernails when I knelt down and clutched at it, praying to the patron saint of hopeless cases St Jude to make this all a dream.

And it does not even ask that most pressing of questions – where was God in all this? The answer becomes more layered as the years pass.

Examining the different processes of truth-finding, history-telling, and formation of collective memory, Professor Chrisje Brants and Professor Katrien Klep conclude: “The legal truth, laid down in the rulings of an international criminal court is, by definition, not open-ended. The verdict of a court is definite and authoritative; in this context, closure, not continued debate about what it has established as the truth, is its one and only purpose – indeed, on this its legitimacy depends. But then, also by definition, its contribution to history-telling, collective memory, and justice for victims is limited indeed.”8

In this regard, the learned writers also point out that “[h]istory and memory change as time goes on, and are never ‘finished.’”9

Remembering the past, then, is not just a scientific and once-and-for-all endeavor of ascertaining the 5Ws+1H. It is also an art of attributing meaning and finding a narrative in the events that have happened.

Beyond the context of transitional justice, there is a word for this art of dwelling on the past: klexos. And of this artform, the Dictionary of Obscure Sorrows echoes: “Maybe we should think of memory itself as a work of art—and a work of art is never finished, only abandoned.”

There are therefore two key elements in klexos: accuracy and meaning.

To speak of accuracy in recording the past is trite. Dates, names, sequence of events – these matter. Research on the fallibility of eye-witness memory highlights the grave consequences when we remember wrongly.

But to think of memory merely as a recording device is misconceived. In Elizabeth Loftus’ TEDtalk on the reliability of memory, she confirms that when we remember, we are not so much playing back what our senses have recorded. Instead, we reconstruct the past.

Beyond the factual data set of what actually happened, we make sense out of our past experiences, we connect the dots, we construct and reconstruct narrative arcs. We infuse an objective timeline with subjective meaning.

The forms that the archives of our lives can take have evolved with the rise of social media. At the most extreme, Snapchat and Stories inveigh against the very idea of permanence, since the pictures and videos (allegedly) vanish forever after some time. Instagram heralded the prioritization of pictures over words. Twitter limited any expression of thought to 140 characters.

Perhaps it is inaccurate to conceive of these social media initiatives as archival tools, since they seek more to share and to capture the moment rather than to reflect on the past. All through a screen, of course. As one article puts it, “For Generation Z, there is no struggle to make sense of things. There is only the impulse to share.”

But there seems to be a counter-movement arising. Amidst the FLFC-culture of our times, slow journalism is gaining ground. A New Yorker staff writer opined: “We binge on instant knowledge, but we are learning the hazards, and readers are warier than they used to be of nanosecond-interpretations of Supreme Court decisions.” In 2015, The Huffington Post launched Highline,10 a magazine dedicated to running only cover stories based on months of investigations. Even our local newpspaper Today now has a section called the ‘Big Read’,11 which publishes longer and more thoughtful pieces.

While speed, brevity, and the power to grab attention will still remain foremost news values, slow journalism recognizes that readers also hunger for insight, for immersion, and for analysis. And the Web is taking notice.

But prose is not the only or even the best medium to archive, to reflect on, or to just make sense of life.

As a blogger, I am naturally a proponent of longform journaling. But as my Gen Z friend (who studies linguistics) counter-proposes, “Just cuz there r fewer words doesn’t mean we think less.”

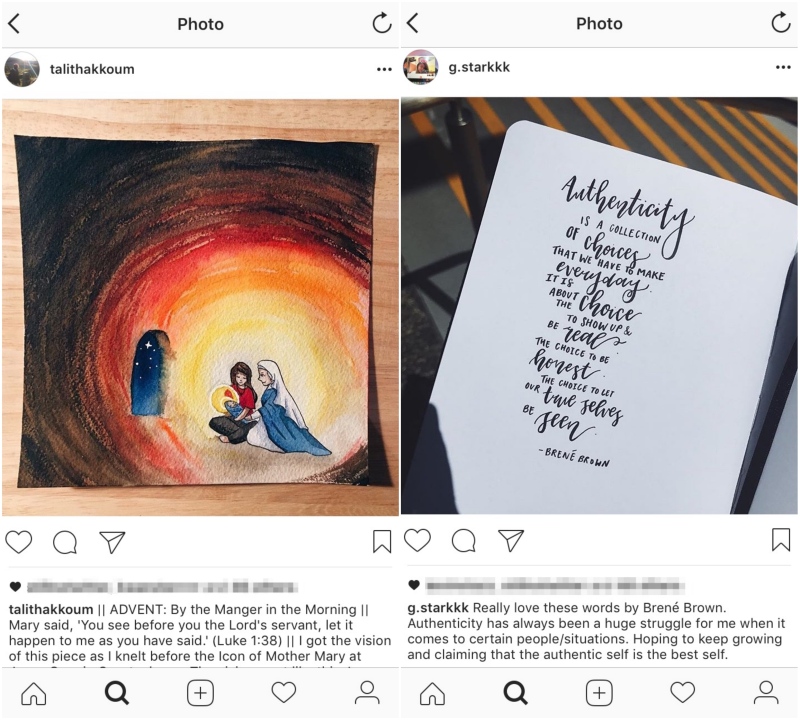

Indeed, many of the Gen Z Instagram accounts that I follow are often filled with musings – be it through photos or captions or something in-between like typography – about life. One 20-year-old I know even has a third account (two is common among Gen Z – one ‘main’ account as a curated public persona and one ‘spam’ account for closer friends to follow) dedicated to more introspective posts.

While sheer wit and conviction certainly drive much of the content that Generation Z produces, not everything is simply “big, colorful, and hysterical”. There is depth and maturity too.

Be it blogging, scrapbooking, or instagramming, a question persists: are we being merely self-indulgent? Archiving the great events or the lives people that have shaped history is uncontroversial. But what of the grain of our own lives, so lost and so insignificant in the sands of time?

Vanity is undoubtedly a temptation, against which the easiest way of resisting is to keep our archives private.

But as Brené Brown says (and the Gen Z instagrammer above quotes), “Authenticity is a collection of choices that we have to make every day. It’s about the choice to show up and be real. The choice to be honest. The choice to let our true selves be seen.”

These words resound with those of us who share regularly: we are honest with ourselves, we share with others, not necessarily in that order. To the extent, therefore, that the sharing of our lives intertwine with our pursuit of authenticity, perhaps we should be willing to endure some pretentiousness as the price of knowing ourselves.

For myself, blogging is many things. It is a way to make myself available to others. When people ask me a question about my life, the lazy (though admittedly lesser) alternative to sharing with them in person is to send them a link. It is also a way to make myself available to myself. It is amazingly convenient to have a compendium of my life to refer to at any time, to frame a more articulate sharing, to recall a personal story for a session, or just to remember what I went through before.

Perhaps, most importantly, it is a way for me to make sense of my world. To echo Gaiman, “All too often I write to find out what I think about a subject, not because I already know.”12

When my dad and I got into another bad accident in August 2014, I wrote about how I had lost faith in miracles. In September, I wrote about how I had to content with finding God in the ordinary, if I could not find Him in the extraordinary. In July 2015, I wrote again, but this time about how the accident formed part of a period of desolation, which was in turn, part of a larger narrative arc of learning to trust God.

The archive of my life thus becomes a lens through which I see the world. And if we can see the world in our grain of sand, we can move from klexos to sonder, to the humility of realizing that every person’s grain of life is as rich and as varied as our own.

Moving beyond the individual, the wisdom of transitional justice underscores that klexos is not only relevant to individual lives, but to communities as well.

Just three weeks ago, I was surfing through our community’s spiritual bucket list, and I realized that some of us have already checked items off the list. To some extent, 1Cor12’s narrative has been captured in Mere Community. BASIC will be celebrating their 10th anniversary soon, and their ten years of journeying together will be digitally engraved into the blogs and Instagram accounts of their members.

Other memories are worth preserving. Consider, for example, OWL’s formation, journey, and eventual dissolution. There are precious shards here that I would love to see pieced together into a panel of stained glass.

Stained glass, after all, is a common sight in the Church.

In the final analysis, perhaps stained glass should be the ideal that all our archives aspire to. Because all our lives are broken and fragmented, and will remain so, regardless of how we curate or scrapbook our memories. It is only when we let Christ’s light shine through our past, into our present, and to guide our future, does beauty emerge.

Perhaps, then, it is not so much the unarchived, or even the unexamined life, but the un-examen-ed life, that is not worth living.

1. Bonjournal is a minimalist travel logging app. It has a clean interface and limits the number of pictures per post to three. I have been using it since 2014, and will probably continue to do so.

2. Lk 22:19.

3. See CCC 1366.

4. CCC 1367.

5. See CCC 1106.

6. Ariel Dulitzky, “Memory, an essential element of transitional justice”, 20 April 2014. He was a member of the UN Working Group on Enforced or Involuntary Disappearances in 2014.

7. Ibid.

8. Chrisje Brants and Katrien Klep, “Transitional Justice: History-Telling, Collective Memory, and the Victim-Witness”, International Journal of Conflict and Violence Vol. 7(1) 2013, pp.36-49.

9. Ibid.

10. See e.g. “Mothers of ISIS“, a paradigm-shifting angle on ISIS recruitment.

11. See e.g. this article covering the glut of lawyers, providing probably the most comprehensive and insightful analysis on the situation.

12. Neil Gaiman, “Some Reflections on Myth (with Several Digressions onto Gardening, Comics and Fairy Tales”, in A View from the Cheap Seats.

___

This article was originally blogged at Mel.

Melvyn Foo is a Singaporean ex-lawyer. He is supposed to be a young adult, but he is really a lot more young than adult. He committed to God while sitting alone before a small and unadorned tabernacle. Since then, everything has pretty much fallen into place. You can visit his blog at http://melvynfoo.wordpress.com/