For this symposium on mercy and killing most of the writers have been weighing in on the issues of euthanasia and abortion, and with good reason. These are the strongest manifestations of our culture of death. They are the most obvious symptoms of a disease that threatens our society, and even our entire race. In this post, however, I want to shed a little light on another symptom of the same disease which is visible only within a niche community, namely the military.

No one needs to be reminded that this country is currently engaged in violent action in several locations around the globe. Whether or not any of those actions are justified is not really the point of this blog. I am not talking about jus ad bellum. What concerns me in this blog is jus in bello. Not why we fight, but how we fight.

We’ve come a long way since the atrocities of WWII (perpetrated by both sides with astounding callousness). In February of 1945 the Allies burned the city of Dresden to the ground, causing some 20,000 civilian casualties, all in an effort to eliminate a major industrial and rail center. Approximately 200,000 civilians died as a direct result of the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki in August of the same year. Both of these actions, although horrible crimes against humanity, were largely uncontested because of the political and historical context in which they took place. In the world we live in now there is no one powerful enough to survive the reaction that would follow such an action. It simply could not happen. The emphasis of the American military on its precision targeted weapons and its surgical strikes is a recognition of the fact that the public behind us will not tolerate massive civilian casualties. Collateral damage is avoided at all costs. Sometimes this reluctance for unnecessary damage leads to a zero-defect mentaliy, imposing unrealistic and impossible expectations.

I strongly approve this hesitancy to kill unnecessarily, but I am not too optimistic about it. My experience of it is that the policies that seek to eliminate civilian casualties are not based on a real love of the Iraqi or Afghani people. The policies exist because the American public insists that they exist. It is a fragile insistence, based on sentiment rather than on knowledge, but it has teeth. Politicians stand or fall based on that sentiment, so rules are laid down out of political expediency, and enforced through fear of punishment. At the ground level, where young soldiers actually make life and death decisions in a split second, there is a tension between the few soldiers who truly do care about the people of the country, the few who truly hate them, and the vast majority who just want to get through the tour alive and go home. At this level the rules of engagement can seem artificial and meaningless, contradictory restrictions placed upon us by officers who don’t want to risk their career by having a civilian death under their command.

The problem is that the Rules of Engagement are ethical guidelines imposed on us from the outside. For most soldiers they are not moral principles that we know in our own hearts. In this regard I was more fortunate than most soldiers. I arrived at basic training with a moral education far more detailed and articulate than even the officers who gave us the Law of Land Warfare briefs. Whereas the bottom line for most soldiers is, “Don’t slip up and get caught killing a civilian because they will fry you,” for me the bottom line is “God, please don’t ever let me use my weapons unjustly.”

The logical conclusion of this pursuit can be seen in the U. S. Military’s robotics programs. Currently the U.S. uses robots for many applications in combat, including surveillance, explosive ordnance disposal, and remote weapons strikes. Some aerial drones are capable of firing rockets, and certain land platforms can be equipped with light machine guns for ground warfare. The advantages of these systems are that they keep American soldiers further back from the line of fire, which reduces the risk of American lives. A Squad Automatic Weapon mounted on a robot and fired remotely is inherently more accurate than the same weapon carried by a living, breathing soldier. The robot eliminates breath control, trigger squeeze, and recoil management, enabling them to fire incredibly tight groups at distance, maxing out the ballistic capacity of the weapon.

Currently all of those systems are under the control of human operators, either a few hundred meters behind them or halfway around the globe. However, research is currently underway to create robots that would operate completely autonomously, with “ethical programming” that would make them capable of making life-or-death decisions in an ethical manner.

It is not a new trend. Human beings have been seeking to make warfare more efficient since the Cain first struck Abel with a rock. The key to making warfare efficient has always been to remove the distinctly human element; remove the fear, remove the hesitation, remove the compassion. LTC Dave Grossman in his groundbreaking book “On Killing” documents the increasing use of enabling factors throughout history to create psychological distance from the enemy. Nothing creates psychological distance like having the human being reduced to a blurry silhouette on a computer screen; all the better if it is in thermal or night vision coloring rather than in true color. Psychological distancing is not nearly so easy when you can look the enemy in the eye and smell his sweat.

I am deeply afraid of this trend. I am terrified of where it will take us, because I have seen where it already has taken us. I know soldiers who want to kick all the video cameras out of Afghanistan and go through the country killing anyone who won’t support us. I know soldiers who wouldn’t think twice about flattening an entire village if there were insurgents hiding in it. When a polish platoon that shared a base with us took some mortar rounds on patrol, their response was to set up their own mortars and indiscriminately drop a half dozen rounds in the nearest village. More than a few American soldiers responded, “Good for them. At least they can do that without going to jail.”

These are not monsters. They are the same guys who would give out candy to the children when we walked through the villages, who would try to make sure the little girls got their share before the boys stole it all. They lack the imagination to see what is really happening. They simply don’t see the people on the other end of the weapon, so they have no compassion. That is the inevitable result of long distance warfare. If LTC Grossman is right, it is the subconscious goal of long-distance warfare.

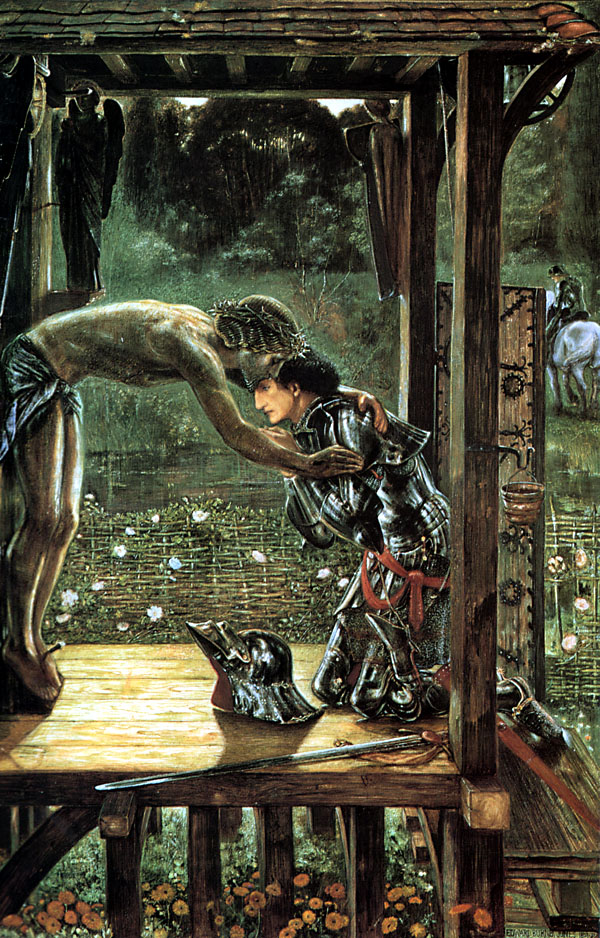

We Americans like to do everything from a distance. We make peace from a distance, throwing money at disembodied problems in Africa and Nepal; and we make war from a distance, throwing billions of dollars’ worth of bombs at our enemies from as far away as we can. This is not a truly human approach. Humans should not be afraid to get their hands dirty with other human beings. If we are, then maybe we should rethink what we’re doing. Even if I can be certain that the person being killed is a bad guy, who seriously poses a threat to innocent people, and can only be stopped by being killed, I still don’t like the idea of him being killed like that, from a distance. I don’t like thinking that some overweight nerdy Air Force kid who played too much X-box growing up now gets to hit buttons and kill people half-way around the world between his coffee and donuts. Even if I could be assured a perfect moral decision 100% of the time I would reject that kind of killing. The person dying is a human being. Perhaps he is Osama Bin Laden or some similar person, who has brought himself to this end by a lifetime of evil choices. It doesn’t matter. He still should not be simply exterminated, squashed like a bug. He still should be given the opportunity to repent, which means he should go to prison if possible. If that cannot be (and sometimes it cannot) then he should die like a human being, not like a cockroach on the ground.

This is the root of my distrust for the modern world’s fascination with the technology of warfare. It insulates us from what we are doing, from the risk to ourselves and the risk to our psyches, but in dehumanizing warfare we eliminate any incentive to end it, or to look for another way. A machine may not be capable of fear or hesitation, but neither is it capable of mercy or understanding.

For a more in depth look at my thoughts on just war:

http://themanwhowouldbeknight.blogspot.com/2012/03/why-i-pray-for-peace.html

http://themanwhowouldbeknight.blogspot.com/2012/03/impersonal-warfare.html

http://themanwhowouldbeknight.blogspot.com/2012/03/another-way-part-1.html

http://themanwhowouldbeknight.blogspot.com/2012/03/another-way-part-2.html

http://themanwhowouldbeknight.blogspot.com/2012/03/another-way-part-3.html

3 thoughts on “Robot Armies”

Pingback: President Obama Newsweek Gay President Gay Marriage SSPX | The Pulpit

Ah, I am studying “Night” by Elie Wiesel in school and my teacher told me that the reason the Nazis swaped to concentration camps was because killing Jews with firing squads was causing phsycological turmoil to the Nazi troops. They wanted a way to kill them without looking at them directly. Creamatoriums and gass chambers were the solution.

Even in those times when we are doing the right thing by fighting, allowing us to distance ourselves from something so grave makes it easier to forget it is a grave matter. If we stop acknowlaging the gravity of death I fear we might be looser in dealing it out as a solution to all our problems.

Pingback: Death is Not a Right | IgnitumToday