To study any subject at depth is, in a certain way, to lose one’s innocence.

Before the Copernican revolution, it was easy, indeed natural, to perceive that the sun, the moon, and nature itself all contribute to a delicate balance that permits human life to go on. After the revolution, although nothing changed about the interrelationship between these elements and human existence, that intuition became increasingly inaccessible to us. At first, we were thrown off by the re-centering of the cosmos; then, the sheer scope of the Universe began to overwhelm us, and we were incredulous that such a vast Creation could have any particular care for us. Of course, we are a very important piece of Creation, and scale is no impediment to the focus of a limitless divine mind. In fact, we can appreciate this truth more deeply we understand the scale of the Universe. But our naivete, our innocent, intuitive grasp of the essence of the subject has been lost in the process of sounding these depths, and is only recovered with difficulty.

The twentieth century saw the first serious attempts at an historico-critical study of liturgical worship in the Catholic Church, although something of the kind was of course attempted during the Reformation as the Protestant Reformers tried to repristinate their liturgies. It seems apparent that, in the course of this study, we lost in a significant way our innocence before worship.

Before this research was done, somewhat lacking in historical perspective, we had been prone to perceive in liturgical worship a received set of rites, from Christ, more or less directly, by which we were to worship God and gain sacramental graces for salvation. This intuition, free of the baggage of historical and critical research, spoke primarily to the why of worship.

Increasingly, however, a more historically-informed Church has become bogged down in questions of the how of worship, in large part because she has come to understand more or less scientifically the distinctions between the essential and non-essential elements of the rites. We perceived first very clearly that the liturgy was anything but a static, that it has been subject to great change and variety across lands and centuries, and we then began to seek a criterion by which such variety and change was to be accounted for, judged, and, at last, proactively employed for the improvement of liturgical worship in our own day. Thus, the pastoral judgment emerged naturally out of the discussion of the history of liturgy, at least in those circles where liturgical worship was still a practical, living reality.

Now, the pastoral judgment is related at its deepest level to the why of liturgy, but it is primarily expressed in terms of the how of liturgy, and its practical effect has been to reincarnate the very rubricism, an obsession with externals to the point of forgetting the essentials, that so many of its proponents had hoped it would help to overcome. I would argue that this neo-rubricism is best felt in a tendency to view worship that is not pastorally perfect as essentially inaccessible to worshippers. No scholar since the Reformation would hold that position strictly, I think, but it is an attitude I have come across time and time again amongst the faithful. It is probably born of a radical change of approach: rather than convincing the worshipper to understand the eternal relevance of worship, placing the problem at the level of catechesis, we instead view the ritual itself as problematic, and attempt to render the worship relevant to the faithful by means of relaxing rubrics and increasing expectations for inculturation.

Attempting to render worship relevant to the faithful: anyone who works in liturgical music, as I do, understands how daunting this proposed task truly is. It is difficult today to imagine a time when a significant portion of liturgical musicians firmly believed that the reintroduction of properly interpreted Gregorian Chant, which was supposed to have to the utmost the quality of “universality” that St. Pius X stipulated be present in all sacred music, would render any liturgy pastorally ideal, but I’m not certain that our present goals are less of a pie in the sky. Now, instead of restoring a universal, timeless ideal, a daunting goal, but concrete, we are called upon to have worship that is contemporary, inculturated, that does not aim too high nor undershoot the faithful, and that facilitates the easy musical participation of the entire assembly, while, according at least to the letter of the law, preserving the “treasure of inestimable value” that is the musical tradition of the Catholic Church, according to the Second Vatican Council.

This implies a positively uncanny ability to read the gathered assembly like a book, to make choices that will speak to, engage, and make the worship relevant to all (or nearly all) present. It comes as perhaps no surprise, then, that some of the most successful liturgical musicians in this new environment, Marty Haugen and Michel Guimont (NPM’s Pastoral Musician of the Year for 2015), have significant background in Psychology as well as in music!

I have been the odd man out in too many choirs and assemblies to believe for a second that it is possible to make the magic choices that will reach everybody. Extend our idea of the worshipping assembly from the weekly, predictable collection of locals to any Catholic whosoever that wanders into our parish for Mass, and we are entirely defeated. Indeed, in most parishes that emphasize this approach, the congregation ends up age-, race-, and preference-segregated:

or perhaps even in age-segregated age-segregated groups:

It has been my experience that over-emphasis on the importance of these choices (which are important to a point) often obscures the purpose of worship, and even highly active, involved, and committed members of the faithful can miss the point of liturgy and worship to an astonishing degree.

As an example, someone I know who is very involved in their parish and who has been entirely formed in this environment of assembly-tailored pastoral liturgy, once told me that they went overseas, and, after a single Mass in that country, quit attending altogether, because they “got nothing out of it,” as it was not in English.

Compare this experience to that of my in-laws, regular attendees of the usus antiquior, who on a recent trip found Mass at a Vietnamese Catholic parish a very edifying experience, despite literally none of the pastoral effort at that Mass having been directed towards them. They were able to see past the externals to the real act of worship in which they were able to take part.

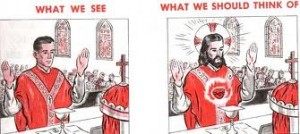

If the rubricism of the past prevented the priest from seeing past the legal requirements for the chemical composition of altar candles to the act of worship he was celebrating, this new rubricism has so obsessed us with the externals of worship that we forget that, as members of the Body of Christ, we are not only entitled, but actually empowered, to participate in any act of the Church’s public worship whatever in the deepest way possible: by joining our prayers to that of Christ who acts in the Liturgy, and by our worthy sacramental participation in the Holy Eucharist, that makes us one in Christ, even if those around us are singing His praise in Vietnamese.

It is possible, as it has been in cosmology, to recover our old innocence before worship, in spite of our knowledge. It is true, Christ may not have worn a maniple or said the Roman Canon. But the rites we have received are indeed from Christ, for worship, and confer grace.

If we refuse to worship because we find the rites irrelevant to us, are we worshipping Christ, or relevance?

1 thought on “The Worship of Relevance”

To answer your question: If we refuse to worship because we find the rites irrelevant to us, are we worshipping Christ, or relevance? We are worshipping ourselves, not Christ or relevance. I attended the Usus Antiquior for myself at first so that ‘I’ would get more out of the Mass but instead it molded me so that now I get much more out of the Mass at the basic Novus Ordo daily Masses. Yet I still find the music distracting at most Novus Ordo Sunday Masses. It seems that it doesn’t act as inspiring back ground music that adds to my prayers, but instead distracting music that draws me away from prayer. I am that way at my work as well. I can’t concentrate when someone is playing music. Yet for some reason, when I visited the Benedictine monastery where they sang in Latin, I found the Gregorian chant seemed to carry me to God. I guess they knew what they were doing in the middle ages.